On Thursday 14 July 2016 a new high-speed rail link between Melbourne and Sydney was announced. The project will be undertaken by CLARA (Consolidated Land and Rail Australia Pty Ltd) as a privately-run railway financed by real estate development along the route.

The new rail line’s business case follows a similar strategy to Hong Kong’s MTR Corporation, one of the only consistently profitable rapid transit networks. Hong Kong’s MTR makes a lot of its money through property development. It essentially builds new metro lines and builds high-rise commercial and residential developments around the new stations making money off the increase in property values that come along with the new metro line.

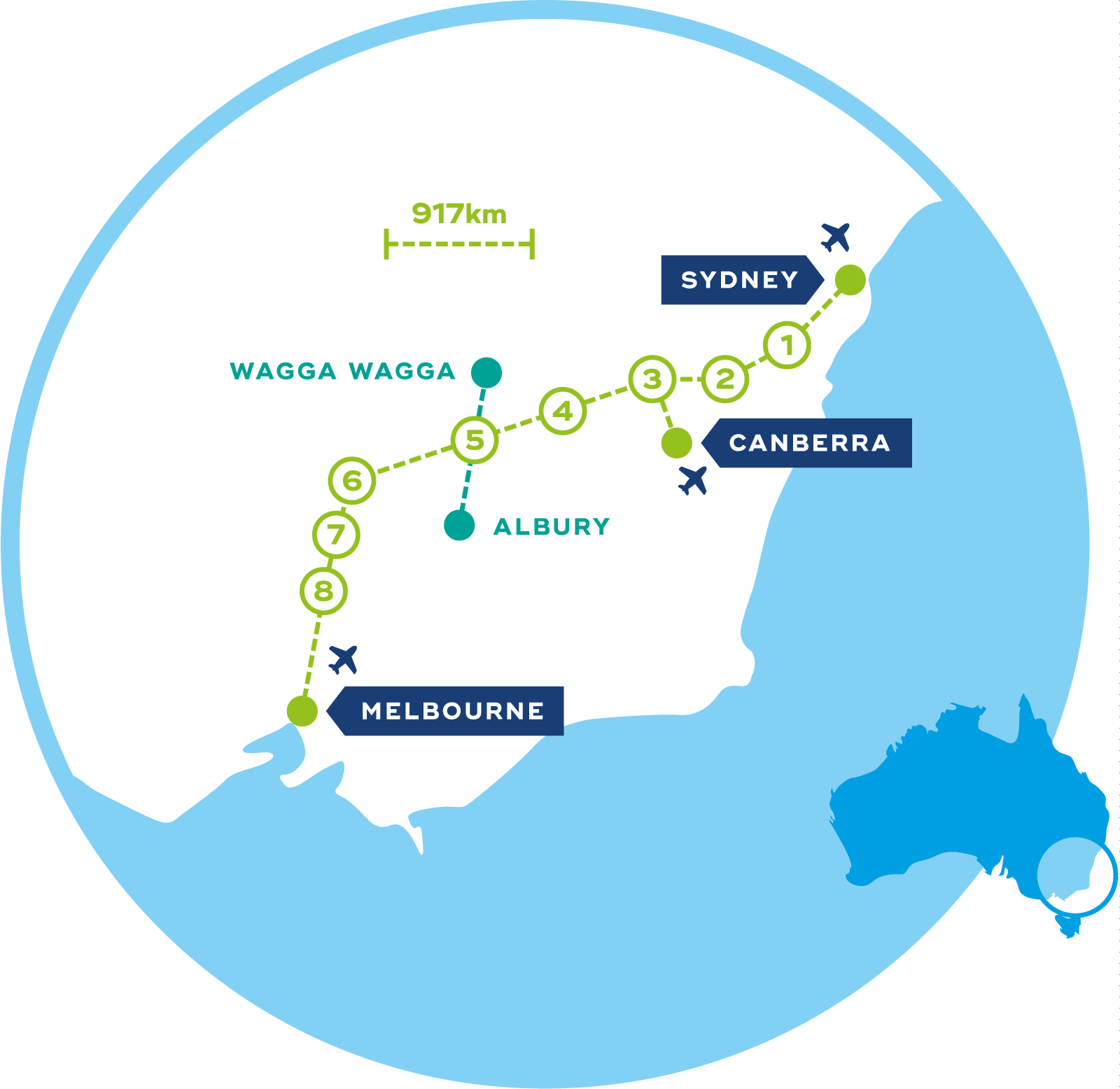

The CLARA plan follows a similar concept, but on a much bigger scale. CLARA’s proposal involves building eight brand new cities along the new rail line. It is an ambitious project but it makes total sense; it is difficult to convince thousands of people to live in a new city without a high-speed rail link to Melbourne or Sydney and you can’t make money from a new rail line without developing property along the route.

It’s fantastic. A brand new high speed rail line without resorting to taxpayer-funding, plus another eight cities to visit en route between Melbourne and Sydney. Assuming that CLARA have learned from earlier planned cities, the new cities will be compact cities with a relatively high population density that will result in a more vibrant urban environment rather than the low density suburban sprawl that characterises most large Australian towns and cities.

When you have cities with a high population density it becomes commercially viable to have a world-class public transport system. Likewise inter-city rail travel becomes viable when you have several medium-to-large size cities located several hundred kilometres apart. The whole system starts to make sense when the new cities are added to the mix.

Over the past 20 years there have been a number of other high-speed rail proposals in Australia, but none of these have amounted to anything. The CLARA plan has a much better chance of success than any of the other proposals, as it is based on a sound business case and most importantly it does not rely on taxpayer funding.

The main drawback with this plan is that it is a long term project that will be built in several stages. It is an ambitious project, but not so ambitious as to build eight new cities at the same time. Although the initial stage, which will see a rail line connecting Melbourne with two new cities in northern Victoria, could be completed within 10 years, it could take up to 40 years before the entire project is complete with trains running all the way from Melbourne to Sydney.

When the project was announced in July 2016 there is limited information about it and even now almost two years later many of the details remain unclear (although some of our initial predictions have proven accurate). Most of the initial news reports read like a verbatim press release, although the Thursday issue of The Australian newspaper after the initial announcment provided a little more information than most other news outlets. When the project was first announced we didn’t know where the cities would be located, what they will be called and we didn’t know how frequently the trains would run or how much they would cost to ride. But there were some clues in the initial news reports and on the CLARA website that allow us to make a few assumptions and more recent media coverage gives us a better idea where the new cities will be located.

The high-speed train

CLARA hasn’t told us what technology they will use, but they have indicated which three they will choose between:

- Super conducting magnetic levitation trains. Maglev trains are the fastest high-speed trains running at around 500 km/h, which would complete the Melbourne–Sydney journey in one hour and 50 minutes. The 400m-long trains would carry up to 1000 passengers and would run through open country on a viaduct above ground level to allow for a level ride (also avoiding wildlife and livestock that may otherwise wander onto the line) and would use tunnels to travel through urban areas.

- Trains similar the the French TGV high-speed trains. These are the fastest wheeled trains, that are tried and tested on routes in France (TGV), Belgium (Thalys) and the UK (Eurostar). The 485-seat trains would travel at around 350 km/h.

- China HSR. China’s high-speed rail network is the largest in the world with operational speeds of up to 380 km/h. The 200m-long trains can carry 548 passengers.

Being late to the high-speed rail game, my guess is that CLARA would opt for the fastest option. The additional expense of these trains is small when compared to the cost of acquiring the land and building eight new cities and the quicker trip would be an added incentive to prospective residents of these cities. The main clue, however, is the CLARA are talking about the express Melbourne–Sydney route taking under two hours and only Maglev trains are capable of this speed.

How much will it cost to ride the new high-speed train

At this stage we have no idea how much it will cost to ride the new high-speed train. However the new cities are being touted as bedroom communities with residents commuting into Melbourne or Sydney by fast train and if your daily commute is by fast train, I would expect that fares would be cheap enough that it would still be cheaper to pay for your daily commute and also live in one of these new cities rather than in the centre of Melbourne or Sydney.

Season passes and multi-ride tickets would certainly be an affordable option for those commuting from the new cities, but one-off tickets and express trains (those not stopping at the eight new cities being built en route) will likely be considerably more expensive with prices in line with airfares between the two cities.

A possible branch line to Albury and Wagga Wagga

The map on the CLARA website shows a connecting line linking one of the new cities with both Albury and Wagga Wagga. This line is shown in a different colour, indicating that this line will not be a high-speed train (of course I’m just speculating here as there is nothing on their website about this line other that what is indicated on the map).

This makes sense, though. This new city – rumoured to be near Henty, NSW – would be the farthest of the proposed cities from both Melbourne and Sydney making it less attractive as a place to commute into Melbourne and Sydney from. However being placed midway between Albury and Wagga Wagga means that residents of these two cities would be able to travel to the new city both for work and also to travel onwards towards Melbourne and Sydney.

An article in the December 2016/January 2017 issue of The Monthly also mentions that this new city would be connected to Albury and Wagga Wagga by secondary spur lines, although it fails to mention whether this has been confirmed by CLARA or whether they are also drawing the same conclusions as ourselves.

Eight new cities

The high-speed train is just part of the CLARA plan, but deep down CLARA is a real estate development company focused mainly on building eight new cities.

Although the exact names of the cities are yet to be determined, the locations have been revealed in an article in The Monthly. The new cities will be located at:

- Sutton Forest, NSW near Moss Vale in the Southern Highlands. In the future this city could have a connecting rail link to Woollongong (a rail line already exists, but is used for a heritage railway).

- Marulan, NSW, east of Goulburn

- Jerrawa, NSW, east of Yass

- The junction of the Hume and Snowy Mountains Highways, south of Gundagai

- Munyabla, NSW, west of Henty

- Tocumwal, on the NSW side of the Murray River

- Tallygaroopna, VIC, north of Shepparton

- Nagambie Lakes, VIC

The first cities to be built will be at Nagambie Lakes (8) and Tallygaroopna (Sheparton) (7) and those between Sydney and Canberra – Sutton Forest (1) and Marulan (2).

Initially not a lot is was known about these cities, except for the following:

- The cities are being dubbed as ‘smart cities’. All this means is that they will be wired from the ground up with high-speed NBN internet (it is not just the trains that will be high-speed).

- Each city will have a population density of at least 6000 people per square kilometre.

- Each city will be initially developed to a minimum size of 5000 acres. That’s around 20 square kilometres.

- 20 square kilometres with 6000 people per square kilometre means that each city will start out with around 120,000 people. That’s around the same as the population of Darwin.

- Cities would be compact and developed with a focus on public transport with around 80% of residents relying on public transport for daily travel and most residents living within 10 minutes of what they need.

- Each of the new cities would be located within 15km of an existing regional town.

Let’s look at each of these factors in more detail:

Smart cities

This is simple really. If you’re building a brand new city, it simply makes sense to lay fibre optic cable under the streets and wire every building with high-speed internet. Not really a big deal, but it may convince some internet-based businesses to move to the new cities.

Smart cities could also refer to the cities being built around universities and research organisations. This is certainly a strong possibility as CLARA’s website indicates that it is working with both CSIRO and RMIT University.

A medium-high population density

There are a lot of things that make a great city and a medium-high population density is one of the main factors here (I will cover other aspects as I expand this post). Think about any of the really great cities (large or small) that you have visited and chances are they had a much higher population density than the average Australian town or city. New York City and Paris have around 20,000 per square kilometre and most European towns and cities have at least 6000 people per square kilometre. In contrast the greater Sydney area has only 350 people per square kilometre and the greater Melbourne area has only 450 people per square kilometre (although the central areas of these cities have a much higher population density).

A higher population density means that a city is more compact and walkable. It means that the corner shop and your local bar or cafe is right around the corner rather than a 15-minute walk away, which would be the case if you lived in an anonymous suburb (in fact if you lived in a suburb you probably wouldn’t even consider walking). When you walk around your neighbourhood, you get to know your neighbours and you live longer. You keep fit and are less likely to be involved in a car accident.

A higher population density means a more compact city. Rather than thousands of square kilometres of countryside being taken over by suburban sprawl, a city with a compact footprint leaves more space for farming and nature.

The big advantage of a higher population density is that you get to live in a more vibrant community. There is a buzz in the air that you just can’t get in suburbia.

120,000–500,000 people

CLARA are proposing to build cities, not towns. The plan appears to start out with a city around the same size as Darwin and grow from there. These cities will absorb some of Australia’s projected extra 14 million new residents (by 2050) while taking pressure off the population growth in Melbourne and Sydney. It would also create vibrant regional cities so people living in regional Australia don’t need to travel all the way into Melbourne or Sydney for shopping and medical treatment.

More recent media reports mention that CLARA expects that these cities would grow to around 400–500,000 people, or around the same size as Canberra.

The optimal size for these cities is between 100,000 and half a million. Any smaller and they’re not big enough to be vibrant places to live and work, but too big and they begin to sprawl and you get issues with traffic congestion and long commutes.

A focus on public transport

These cities will be built around public transport facilities so most residents won’t even need to own a car. When cities are compact with great public transport, you need never be more than 10 minutes away from anything you need.

Close to existing regional towns

According to a report in The Australian, all the new cities will be located no more than 15km from an existing regional town.

This has benefits for both. A densely-populated city is not for everyone, particularly those who are usually attracted to life in rural Australia. Those people who work in the new city but want a large house on a big block of land will move to an existing town nearby and commute from there. I would expect that the new city’s public transport network will most likely extend to nearby existing towns so commuting between the two will be a practical option.

Early criticism of the project

Any major project is bound to attract criticism. Even less than a week after the project was announced, the following objections had been raised:

Canberra’s new station will be near the airport

A valid criticism, but Canberra’s current train station is hardly very central either and Canberra Airport is not really that far from the city centre, although it does need better transport links (and not just an overpriced airport bus).

It wouldn’t be a big deal to extend the line to Canberra’s current train station and there is always the option of tunnelling to an underground railway station under Canberra city centre.

Existing regional towns are being ignored in preference to the new cities

If it weren’t for the new cities, the project wouldn’t be financially viable and would be difficult to gain approval for as local residents would always find something to object to. Building the rail line where there are no local residents solves this problem.

People who live in regional towns live there because they like those towns the way they are and would rather not live in a larger city. If the railway came to a small town and transformed it into a much larger city (perhaps 10-times its current size) then there would surely be local opposition and the project wouldn’t get off the ground.

The new cities will be much larger than the existing regional towns and the existing towns near the new cities will benefit from the project while retaining their character.

CLARA will make money from this

It seems that whenever a private company tries to achieve something that the government has been unable to do with public funds, then someone gets upset because someone is making money from the project.

The Greens, who you would expect to support a project with a focus on improving public transport and reducing suburban sprawl are opposed to the idea simply because there is a business that will make a profit from the project.

People who oppose projects like this simply because someone is making money need to realise that the best way to build a big infrastructure project like this is not by gouging the taxpayer to build something that people don’t know they need, but by making something people deem an improvement over the status quo (vibrant cities rather than dull suburbia and convenient public transport rather than traffic congestion and parking hassles) and also by making it profitable. If there is money to be made, the private sector will step in and make it happen.

Planned cities never work

Proponents of this argument point to planned cities like Brasilia, Canberra, Milton Keynes and Telford. Which are not exactly noted as vibrant cities.

But the problem isn’t that they are planned cities, but that they were planned in the 20th century with lots of big roads, roundabouts and parking; but not much thought given to creating a walkable environment. But that’s not to say that all planned cities are failures.

Planned cities designed in the 19th century or earlier are very different. They are designed to be walkable, vibrant communities. Adelaide and Melbourne are planned cities, as are La Plata (Argentina), Austin (Texas), Guadalajara, Manila, Mexico City, Philadelphia, Savannah (Georgia) and Washington DC. Even Versailles is a planned city.

Recent Comments